I’ve been playing turn-based RPGs since kindergarten, when my parents brought Super Mario RPG back from the rental store (they thought it was a typical Mario platformer) and unintentionally impacted my tastes in gaming forever. Since then my favorite RPG franchise has unquestionably been Final Fantasy, but after the shift from turn-based to action combat the series lost its juice. The trappings are there, and it certainly hasn’t been bad, but Final Fantasy XVI still felt reactionary, like Square Enix was following industry trends rather than using FF to again revolutionize the genre as they’ve done numerous times in the franchise’s history. Why do I begin with Final Fantasy? Because in Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 I have finally found the game Square Enix has been incapable of making for some fifteen years. This mature, dark, and powerfully human story — the first game by rookie studio Sandfall Interactive — fulfills the promise once kept by Final Fantasy, no less than a genre-defining outing that synthesizes turn-based gameplay with action RPG elements more holistically and successfully than anything I’ve seen before.

The broad strokes of the game’s plot, as told by Tom Guillermin, Co-Founder of Sandfall Interactive and Lead Programmer:

Our story is set in a fantasy world inspired by the Belle Époque, France. Once a year, the Paintress wakes to paint a cursed number upon her monolith and everyone of that age instantly turns to smoke and fades away. She first appeared 67 years ago, and year by year, that number ticks down. At the start of the game, she wakes and paints “33.”

Once yearly, a group of people dedicated to breaking this accelerating cycle of death carry out an Expedition to reach the monolith and kill the Paintress. No Expedition has ever been successful, and none have even so much as returned from the journey. It seems as sure a death sentence there ever was, but “Tomorrow Comes” as the Expeditioner saying goes. In the game’s prologue we meet Gustave, our first party member and the energetic heart of the titular Expedition 33, a man convinced this will be the year the cycle breaks. We see the annual departing of those marked for death by the Paintress, referred to in-world as the Gommage, and then Expedition 33 sets sail and the game begins in earnest. That is about all that I can write about the story while remaining spoiler-free. What follows from here is nothing short of astonishing, a portrait of grief and the ways that it consumes us that is as nuanced, well-written, and sublimely performed as anything I’ve seen in a video game. Each character’s method of grieving is at once completely understandable and entirely reprehensible — there are no easy answers to be found in this world, and the choices they (and we the players) face at the game’s shocking conclusion left me reeling for hours after the credits finished rolling. Do yourself a favor: if you haven’t yet had the plot and its many twists, turns, and revelations spoiled for you, keep it that way at all costs. Go in with a clean canvas and let the paint wash over you however it will.

Video game dialogue is a perpetual thorn in my side. It ranges from rote to ridiculous, and very rarely does a game’s script sound like anything that would realistically come out of a human’s mouth. Clair Obscur is a rare exception to the rule. In the game’s ample runtime, there were nearly no false notes in the script itself: no stupid one-liners ripped straight from the pages of Marvel Studios schlock, and no two-dimensional characterizations — even the oft-repeated item collection or overworld interaction lines never managed to become irritating. The game takes time with its character development and is all the better for it. Mysteries and big-picture questions about each person and their motivations are served up early and then patiently unspooled before major conversational bombshells can be dropped at precisely the right moment. I was also particularly impressed with an optional romance between two of the party characters that played out in a more mature and interesting way than we usually see in the world of tentpole releases. The voice cast is unimpeachably excellent, and includes work by Hollywood stars Charlie Cox and Andy Serkis, and industry regulars Ben Starr and Jennifer English. It’s telling that voters for The Game Awards vested Clair Obscur with three nods in the performance category (part of a record-setting 12 overall nominations): Cox, Starr, and English, with the latter two also sweeping the performance categories at the Golden Joystick Awards. Top to bottom, this game made me go all-in on its full cast of characters, and spared no expense in making me both love and regret that choice in equal measure.

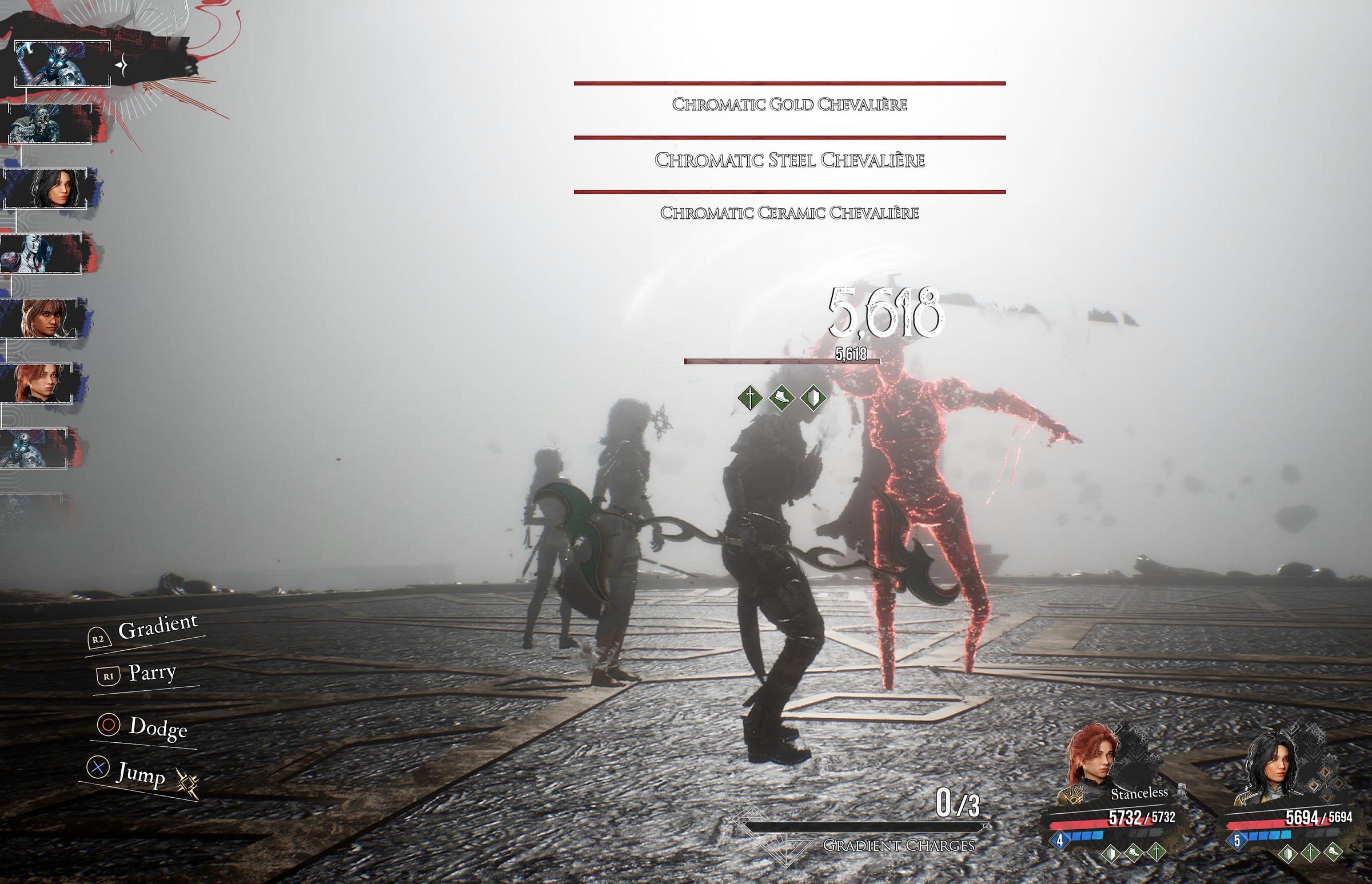

The world of Clair Obscur is gorgeously realized in vivid colors and surreal, often bizarre imagery that looks like something out of an impressionist painting. As the world was ripped apart 67 ago during the Fracture, detritus from various locations around the Continent frequently appear: buildings broken and half-submerged in the sand, remnants of disparate societies jammed together helter-skelter, rock formations frozen at the moment of devastation still half-exploded. Friendly Gestrals can be found dotting the landscape, a race of wooden paintbrush-headed goobers that are perpetually spoiling for a good fight. So, too, can be found the grotesque Nevrons that make up the game’s deep roster of enemies. Some resemble impossible architecture with polygonal heads folding in on themselves, some towering leeches that perpetually drool bile from their gaping mouths, and some twisted marionettes that wiggle and contort and fall over themselves to attack the party. No two are the same, and no two have identical attack patterns — important to note for a game that places combat skill at a premium. The game’s use of color and light to paint its landscapes is breathtaking. One moment you may find yourself in a forest of stark white earth with blood-red leaves and trees; another, an open-air coral reef in vibrant sea tones dancing with sunlight as though it were refracted through water. Later, a devastated city in muted blacks and greys with gargantuan gleaming swords impaled into the ground that drip as though made of molten gold. Something that struck me after a number of hours was the complete absence of any HUD elements. The party’s current status and remaining consumable recovery items can be seen at the press of a button, but quickly gives way back to unfettered visual access to the game’s lush visuals, each frame soaked with pigment like a living canvas. And forget about a minimap — this game doesn’t feature area-specific maps at all. Once you leave the overworld, only your eyes and your memory will serve you in navigating through an area. Even in combat the game wastes no time getting the menu out of the way so you can watch the action unfold without visual disruption. For the contingent of anti-HUD and anti-minimap gamers out there, this is a dream come true.

Perfectly complementing the visual presentation is a stunning score by Lorien Testard that deftly carries us through the experience, punctuating a quiet moment with subdued strings, sweeping us through exotic locales with melodic gusto, and knowing precisely when to spend its pennies on symphonic rock set pieces that are unbelievably fucking awesome. Seriously — in the span of just an hour’s time you will get everything from smooth jazz saxophone, to haunting piano, to electronic synth, to funky bossa nova, and none of it ever feels remotely out of place (in part due to Alice Duport-Percier’s soprano vocals almost stitching the soundtrack together). Each piece belongs neatly to its corresponding area, as though it was extracted like raw essence from its spiritual marrow. The score also provides some delightful little world-building touches for the keen listener to discover. One memorable area featured a mesmerizing repeated vocal line that I initially thought was meant to evoke the area’s boss, a hypnotist of sorts; on a later return after having dispatched said enemy the vocals had been replaced by an instrumental melody, and I realized that this means they had been coming from the boss itself — not an evocation of her, but her actual voice. This granular attention to detail shows up in so many other aspects of the game’s world building that to specifically note them all would require a separate review. Suffice it to say it is as beautiful, strange, and enchanting an audio-visual world as you’re likely to encounter in a modern video game.

Mechanically, Clair Obscur is a megamix of the best ideas from decades of RPGs mixed with a heaping helping of Dark Souls. On its face combat appears to be typical turn-based fare, with turn order visible in the top-left corner of the screen. On their turn, every character can use one of a limited number of shared, rechargeable recovery items, attack, or perform one of their unique skills by spending Action Points (AP), which are accrued through various in-battle methods. Skills require action commands to execute properly and failure can quite literally blow up in your face, which keeps you on your toes even during routine attacks. Each party member features a distinct ability system that requires you to think critically about how their various skills interact with one another. Gustave can build up an overcharge gauge by spending AP on skills that allow him to deal devastating damage in a single blow; Maelle’s skills cause a switch between defensive, attack, and virtuose stances that each offer various situational benefits; and Lune’s elemental skills generate “stains” that can then be consumed by other skills to juice their damage or provide additional benefits. My “a-ha” moment realizing just how well these work together came during a prolonged boss fight in Act 1 in which I got into a flow state with Lune, generating and consuming stains to boost damage, heal my party, and steal an extra turn…pure jazz, man — pure jazz. Six skills can be equipped at a time, and each character’s skill tree is chock-full of unique abilities that interrelate in various ways. Stacking my chosen skills together like Legos to attempt to build towards devastating damage and status effects was a greatly satisfying mental exercise, almost as entertaining as actually watching those strategies play out in combat.

To augment these bespoke skill systems, characters can equip up to three Pictos, which each have a battle-related ability and a passive stat buff, and after mastering said Pictos can equip the battle ability to any party member for a certain number of points called Lumina. The party starts with single-digit Lumina points, but by the end of my playthrough I had increased that amount to over 330 apiece using consumable items found or purchased throughout the journey. Despite that relative embarrassment of riches, the game doesn’t break open easily — I still had to weigh each boss encounter to optimize my ability loadout, maximize the Picto’s passive buffs to cover each character’s stat deficiencies, and make sure that it all moved in concert with their currently-equipped skills. The game contains 193 Pictos, with only a small handful sharing battle-related skills, and each one containing a different passive stat buff combination. The combination possibilities are enough to make your head spin. I went all in on parrying every attack on defense, and accordingly dumped Lumina points into abilities that would reward each counterattack with boosted damage, extra AP gain, and health restoration. Want to play it safe and dodge every attack? There’s a Pictos loadout that will reward you for your prudence. If you want to spec a party member as a healer, you can create a loadout that adds buffs or shields to each healing ability or consumable healing item use. Want to start the battle with buffs already active? There’s a loadout for that. If you want to create a debuffer, you can create a loadout centered on applying detrimental status effects on base attack, extending them multiple turns beyond normal limits, and making the debuff more effective than normal. For the true sickos out there who like to live on the edge, there is even a Pictos that will set your character’s max HP to 1 in exchange for a 100% critical hit rate — then for good measure you can spend your Lumina points to throw on a dozen or so abilities that increase damage, break damage, and provide burn on critical hits to get as much out of every attack as you possibly can. The possibilities are nearly limitless. I probably spent 10 to 15 percent of my total playtime in the Pictos menu, and I never tired of poring over the list and playing mad scientist with my party of Expeditioners.

But offense is only half the equation in Clair Obscur, and I would argue the defensive system is where the game really transcends typical turn-based fare. On each enemy turn, party members can either dodge or attempt to parry the incoming attacks. Each has its strengths and weaknesses: dodging has a more forgiving window, but parrying a full enemy combo allows for a single-player or party-wide counterattack. It’s a great push-and-pull between keeping your party alive for longer at the cost of extending the duration of battles, or racking up damage exponentially faster while constantly at risk of getting wiped out on a missed window. Hitting a parry is a satisfying tactile experience, with an audio-visual pop on the parry itself punctuated by a slow-motion cinematic counterattack that makes you feel like a god. And make no mistake — even rank-and-file enemies will escort you to a premature Gommage if you aren’t on your shit defensively. All the loadout fiddling in the world won’t save you if you can’t dodge and parry effectively, bringing a thrilling level of punishment to a section of combat that’s historically been spent sneaking a sip of soda while you watch your party take a licking. “Getting good” on my parries early on allowed me to grind out optional bosses that I had no business beating with a low-level party and then equip the dropped weapon to bust open the difficulty of the main story, giving me a deep satisfaction the likes of which I’ve only ever felt in Dark Souls. Mark my words — in five years’ time, this turn based-meets-Souls system is going to be everywhere, and I couldn’t be happier about that.

If any of these mechanics feel familiar, it’s because you’ve probably seen them individually in other iconic turn-based RPGs across the decades. For example, the Pictos/Lumina system feels a lot like the badge system from Paper Mario (you know, when those games were actually RPGs) crossed with the magicite or ability system from Final Fantasy VI and IX, respectively. The “timed hit” system of defense technically goes all the way back to the aforementioned Super Mario RPG on the Super Nintendo, and has appeared in plenty of other games since. But it’s not the novelty of each individual element that makes Clair Obscur shine — it’s how Sandfall streamlines, improves upon, and then asks you to engage with these systems in concert with one another to be successful. Sure, we’ve seen action commands in games hundreds of times — but how many missed defensive timed hits in Paper Mario wipe your party in a single shot? Dialing the punishment up to 11 makes even routine button presses a life-or-death affair, which means each combat encounter feels correspondingly more important as a result. The Pictos/Lumina system makes it faster and easier to build and toggle loadouts than its predecessors, getting us into battle to test our strategies rather than requiring hours of grind just to reach that point. These are welcome quality of life improvements that respect players’ time rather than artificially inflating the duration required for a playthrough. As an aside, Sandfall even weaves this mechanic into the story’s lore: one of Gustave’s key inventions is the Lumina converter, which extracts the benefit of each Pictos for use after a certain amount of chroma is gathered from slain foes. Who takes the time to weave the niceties of their battle system into their world-building? Then, when you feel comfortable and confident in each interlocking system, the optional bosses in the late stages of the game (especially the lone superboss) stand ready to push you to your limits in executing the plans that you’ve so carefully laid for your chosen party.

Sandfall’s confidence in their battle system extends to how they conceived of the game’s optional side content: literally everything in this game boils down to combat in some capacity. Every side quest in the game will inevitably result in a fight, usually a miniboss encounter that sits satisfyingly above the main game’s current difficulty level. There are also minigames aplenty and they each center one of the game’s combat mechanics. Playing volleyball with a kooky Gestral? Use the first strike ability to knock baby Gestrals back over the net. Need to open paint cage treasure chests? Use the free aim shooting mechanic to blast the corresponding locks on the overworld. Gotta learn how to dance, or prove your might to a seasoned Gestral warrior, or teach a Nevron with a trumpet which of his sounds are pleasing to the ear and which will make heads literally explode? Parry strings of attacks without missing a single one (or dying). Periodically progressing character relationships at camp results in unlocking the most powerful combat abilities in the game, a nice touch that makes these conversations materially worth investing in. Even the game’s shopkeepers — Gestral merchants found all throughout the world — have special gear that will only unlock if you kick their ass in a 1v1. Rather than making you do a rote fetch quest to unlock it, they just ask if you want to throw hands. Incredible. No notes. If you know you cooked, then steer into it — find a way to build everything around it.

I have very little to say in the way of constructive criticism, but the occasional use of platforming as a movement mechanic is genuinely bad — it’s never clear which edges are catch-able, whether or not I’m making enough contact to catch them, or if landing after a jump will be static or result in a roll that careens me off the face of a cliff and all the way back to the start of the segment. Mercifully this is deployed almost exclusively in optional content, and sparingly at that, so the choice to suffer through it is entirely my own. Whatever else shows up enough to warrant complaint is pretty typical AA first-time-dev stuff: some clunky geometry here, a one-time crash there. An altogether too heavy-handed use of bloom — the one element marring an otherwise spectacular art direction! — almost never rises beyond the level of minor annoyance, although one particular optional combat arena did create legitimate issues reading enemy attacks. Ultimately, what the game does systemically and narratively is so well-conceived and executed that quibbles over a few slightly rough edges are not enough to affect my nearly 90-hour experience in any meaningful way.

Verdict

From my first steps on the game’s overworld, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 felt like coming home again for the first time. Featuring one of the best scripts the medium has ever seen, a devastating narrative that will engage you and keep you guessing from start to finish, and a revelatory battle system that feels like a combination of the best that turn-based RPGs and Soulslike games have to offer, this is not only my 2025 Game of the Year — it is a generational offering that will shape a genre for years to come. Sandfall Interactive will learn to smooth out those rough edges, but in the meantime this rookie outing is not to be missed.

🥖